Robert Snell, Art Historian 2010

Published in hardback: Apollo's Eye and the Four Seasons

At the beginnings of Western philosophy were the Greeks. At the beginnings of Greek philosophy, about two and half thousand years ago, were the so-called Pre-Socratics: Thales (c624-546 BC), who held that the origin of all things was water (a view shared in Hindu philosophy); Anaxamander (c610-546 BC), for whom the world floated free in space, and all the phenomena of life emerged from a primal 'Boundlessness'; Anaxagoras (c500-428 BC), who believed that everything, large and small, started in an original mixture which was set into rotary motion by Mind, Nous. Like a centrifuge this motion separated things out and created the cosmos; at the same time everything, in this account, remained fundamentally interconnected. The Pre-Socratics' passion for understanding the macro and the micro, the light and the dark, the revolutions of the stars and the seasons, drew on immediate experience, perception, and bodily sense, especially of movement and of gravity, as well as on deductive reason.

Adrian Hemming's passion is of a comparable order. His is the Nous of an artist: the intelligence of hand, eye, thought, emotion and bodily sensation in concerted response, mediated through his relationship to his materials, to the physical landscape. This is no mere optical landscape, like that of the snapshot, any more than the universe of the first Greek philosophers was just a dry representation. On the face of it, Hemming's paintings might seem to fit into the currently fashionable category 'abstract landscape' – they might indeed be considered supreme examples of it. Yet to frame them in this way would be to distance and delimit them; the paintings do not 'abstract' from anything. It might dampen the spectator's response to their invitation to get involved.

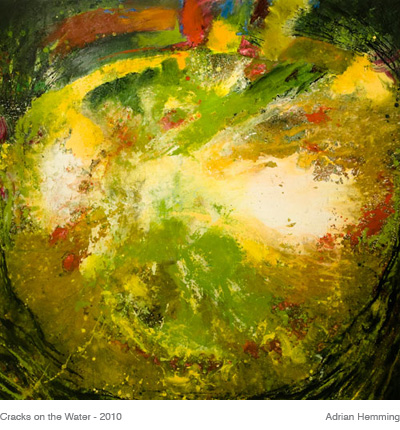

The source of Hemming's recent canvasses is a pond in Jersey, a green island in the grey-green English Channel far from the (to Northern eyes) startling blue of the Mediterranean. The four large, square 'Apollo's Eye' paintings slip, slide, swirl and crack; it is as if we were witnessing a cosmic birth. A pond is a microcosm, a universe in microscopic miniature, a primal, evolutionary soup. It is a self-contained eco-system, with its own internal, thermal currents. The wind also stirs and patterns its surface. It carries reflections of its near and distant environment, of surrounding vegetation and of the day and night sky. It is easy to fall into a pond; the biographer Richard Holmes, writing about William Herschel, the great modern successor to the Greek astronomers, felt a 'kind of cosmological vertigo' when he first looked through a big telescope, as if he were falling into the night and might drown.

The title 'Apollo's Eye' is profoundly suggestive. It comes from a book by Hemming's friend the geographer Denis Cosgrove. In Greek mythology Apollo is the god of the sun, of cosmic order, as well as of the arts. He is the guarantor of the dawn and dusk and of the cycle of the stars and the seasons; his power is awesome. He lent his name to the United States' space programme in the second half of the twentieth century; the first astronauts saw with their own eyes what had been known or intuited from the beginnings of written philosophy, that the earth is an orb held in boundless space, fissured, textured, and divided into primary masses of land and water. The Apollonian eye is also that of the artist, a window into that human mind which has the power to imagine, as well as to analyse, to feel with, as well as to gaze from a dispassionate distance, to bring to life, as well as to organise its own destruction. Adrian Hemming's art allows us, if we can bear the vertigo, a glimpse into our own nature and origins; in the face of the alienating, whirlwind distractions of globalisation, his paintings, in their intense physicality, re-ground us in a real sense of wonder.

Robert Snell, February 2010

Denis Cosgrove, Apollo's Eye. A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, 2001

Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder. How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science. Harper Press, London, 2008, p119

Catherine Osborne, Pre-Socratic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004