Denis Cosgrove 1997

Professor of Human Geography, Humboldt Chair, UCLA, USA.

(Published in the 1997 exhibition catalogue 'Landscape & Memory', Davies & Tooth, London)

April is the cruellest month, breeding lilacs out of the dead land, mixing memory and desire, stirring dull roots with spring rain.

The first lines of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land parody the opening passage of the Canterbury Tales where Geoffrey Chaucer celebrates showery April as the month when watery nature labours to raise life and colour from a cold, dead earth, to make landscape. 'Then do folks go on pilgrimage,' that medieval precursor of modern journeying to distant places. Like pilgrims in their time, travellers today are not the same breed as explorers, whose destinations remain shrouded and uncertain until they are found. For both the pilgrim and the modern traveller the goal of their journey is known; they travel as much for the soul as for the body. In their encounter with distant and unfamiliar but desired places, travellers themselves are remade and landscapes are carved into memory. For landscape does not really designate the world we inhabit in the present of our daily lives; it is not the scenery of home and today, Landscape captures and creates those known but exceptional, desired but unattainable, worlds we see and admire when away from the familiar: journeying physically or imaginatively, in anticipation or memory. Landscape pictures worlds that mix memory and desire.

The landscapes exhibited here come out of Adrian Hemming's travels and journeys, desired places and scenes, remembered in their rendering as studio images. They recall and record pilgrimages much further afield than Eliot’s London or Chaucer's Canterbury. The dry, red heart of Australia, the windblown, late-summer limestone fields and promontories of Aegean Skyros; and the sweating decay of Mayan Mexico: these are Adrian Hemming's places of desire, journey and memory. Elementally different, each of these regions demands from him a distinct imaginative response, an investment of energy which is corporeal as much as it is imaginative. For neither those places themselves nor the images they have yielded here are easy landscapes to inhabit. The memories embodied and evoked by Hemming's pictures are distinctly physical: recollections of the elemental presence of hard rock and insistent wind, heavy heat and soaking moisture, pressing in upon the body and its senses, And in this they speak a truth about the quality of all journeying as pilgrimage. For leaving home, departing from familiar ways and scenes in search of desired places, even today entails discomfort: sleep disrupted, guts protesting, legs aching, feet blistered, neck sunburned, face ravaged by mosquitoes. Intense body sensations are the inescapable companions to wayfaring in pursuit of the strange, the spiritual, the spectacular in the world. They intercept the view of Ayers Rock, they slow the clamber up Palenque's giddying temple steps, they disrupt the island siesta on Aegean afternoons. In memory, these discomforts are lost to consciousness but the body remembers. And Hemming's pictures work precisely in the measure that they speak directly to landscape as sensuous memory, effective at the point where the human body confronts directly the body of nature.

While man has within him a pool of blood wherein the lungs as he breathes expand and contract, so the body of earth has its ocean, which also rises and falls every six hours with the breathing of the world; as from the said pool of blood proceed the veins which spread their branches through the human body, so the ocean fills the body of earth with an infinite number of veins of water.

So landscapes don't come easy. Adrian Hemming's physical labours in landscape are always evident in the final image; memories resonate at the very surface of his paintings. He ploughs materials across his canvases, scraping and layering paint with fingers, palette knife, brush. Confronted by the topography of oils and glazes that texture these landscapes, I am put in mind of a roughly worked field prepared for cultivation: here wet in late winter with clods of sticky clay reflecting metallic blue against a dull, blustery sky, there dry and terracotta red between old olives under a fierce August sun. And I recall that the English word 'labour' comes from the French to plough, or dig, or dress vines, in other words to work a recalcitrant material nature up into humanised landscape. The eye is drawn close into Hemming's laboured fields of colour and texture. In Ghost Gums and Sacred Sites the matt finish of a wide grey-black surface absorbs the gaze as effectively as it swallows all illumination, while a braided trail of glazed whites and yellows, curving through empty space and glancing off the burning rocky ribs - 'dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit - is sticky with glutinous moisture.

Light falling differentially across the surface pigments is a structuring feature of many of these landscapes. Light and colour rather than figure and form compose Hemming's images. This is fitting; for he is less interested in the figurative details of landscapes than in the material resilience’s which force them into memory. This produces disturbing effects on canvases whose landscape images often have precisely the strange familiarity of a place simultaneously desired and remembered. In the Australian works this is apparent in the intensity of a red, yellow and vibrant blue palette that recalls Eliot’s heap of broken images, where the sun beats, and the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, and the dry stone no sound of water. Only there is shadow under this red rock...

But the shadows cast by the skeletal geology of Hemming's red rock yield only the gnarling trunk of ancient eucalyptus, gum trees congealed across the canvas. At Skyros, a happier palette, varied and more detailed, hints at walled and terraced fields, at distant limestone mountains, at lucent beaches and the sea. But this too is no locus amoenus, no dreaming island of lotus eaters. These are 'only the wind's home,' the swept-over fields of a dry meltemi wind that raises whorls of dusty colour across the reticulated surface.

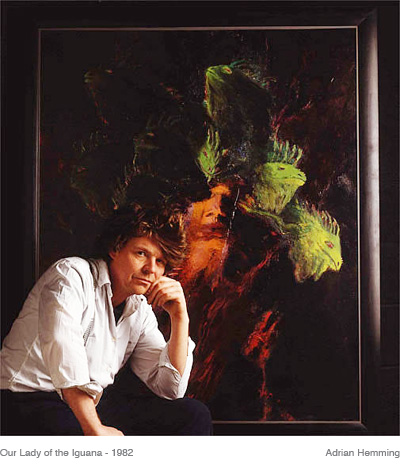

In Hemming's Mexico landscapes it is fire rather than earth or air which informs the image. Not a comforting, warming fire, nor the dry, crackling flame of desiccated eucalyptus or olive, this tropical fire smoulders unseen below the surface of the landscape, glimpsed or smelled as smoke without flame in the heavy shadows on Monte Alban, or in the rain forest of Campeche. Hemming's black and bitter-sweet chocolate palette hints at a desire that burns alongside memory in his Mayan pilgrimage. Journeying to the furthest reaches of space has long been associated imaginatively with pilgrimage to the origins and ends of time, our own time and the earth's. So these landscapes have an eschatological feel, they speak of human ends and destinies. A degree of fear and menace is present among the organic ruins of decayed and overgrown temples and courtyards; fear is explicit in The House of Uxmal the Priest, menace glows in the green, prehistoric reptiles that circle the head of Our Lady of the Iguana.

But Hemming's landscapes do not only recall actual journeys to specific geographical locations. They speak also of those processes through which nature itself labours to form and shape living landscape, and most powerfully of water, the elemental inspiration for Deluge II, for the great diptych Descending Temperature Cline and for the set of smaller blue pieces that derive from these two. As Chaucer's and Eliot’s poetic openings both acknowledge, it is water that brings life to the earth: water falling as rain, water flowing in streams and rivers, water soaking into the warming, vernal earth. Comparing the globe as a living organism with the human body, Leonardo da Vinci saw water as the life blood of earth:

Leonardo was fascinated by the power of water. He writes in his Notebooks of the destructive force of torrential floods, familiar to him as waters breaking the banks of the Val d'Arno from spring storms in the deforested Apennines, or as snow melt swelling the Alpine rivers and violently irrigating the Plain of Lombardy: 'against the irreparable inundation caused by swollen and proud rivers no resource of human foresight can avail. Many landscapes, Tuscany and Lombardy among them, are of course the outcome of human engineering, efforts to confine, regulate and direct the flow of water. Among Leonardo's own engineering sketches is a finely observed study of the effects of a weir on the flow of the River Arno, part of a project to control its flood.

The greatest of all floods, the Biblical Deluge, especially fascinated Leonardo da Vinci. It offered the only possible explanation he could see for the marine shells found high in river valleys and he made a number of studies of downpours so violent that they transform the earth. One of these, the allegorical Cloudburst of Material Possessions of 1510 is the inspiration for Hemming's Deluge II. Hemming has ignored the shower of manufactured objects that make Leonardo's image so strange, in order to concentrate upon the violence of moving water volumes themselves. An intense burst of energy in the top right of Deluge II propels blue across the canvas. Water drenches vertically, as effective as any spring rain; it soaks an indigo dye through the central sector of the canvas and it floods in a snaking course of blue glaze edged in white foam, across the limpid pool which fills the left part of the image.

In The Waste Land, Eliot’s Sweet Thames flows through the landscapes of London rather more softly than Leonardo's deluges rain down upon Florence or Milan. Material possessions too are absent for Eliot:

The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers, silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed...

The smooth currents of Hemming's blue rivers are similarly clear, freed from memories of human folly to confront natural processes unmediated by records of conscious agency. They flow swift and deep across the canvas. The smaller diptychs concentrate with progressive intensity on the passage of blue currents, inviting us to sink below the surface and recover memory in the depth of colour.

Like conscious remembering, painting landscapes in the conventional sense of representing natural scenery is an attempt to secure the changing textures of surface topography, the moving forms of clouds in air and water on the ground, the shifting light of atmosphere and to compose these forms and effects into a single image, harmonious perhaps, or disturbing, sublime or melancholy. But as the historian Simon Schama insists in his book, Landscape and Memory conscious remembering is historically less significant than the visceral memories registered sensuously by the human body when we seek to explain landscapes' capacities to move us individually and to provide the raw materials for powerful, collective myths. Schama's rich text offers an appropriate title for Adrian Hemming's powerful exhibition of landscape images. For the works displayed here are no more landscape paintings in the conventional sense than they are records of conscious remembering. They address directly that intense, often uncomfortable, level of body memory where the forms and processes of an insistent nature press close into a physical human presence. They register the hard labour demanded by aesthetics in nature, aesthetics which are true to the root meaning of aesthesis: 'the perception of the external world by the senses.' And it is in this bodily labour of the senses that nature is remembered as landscape.