Mary Rose Beaumont. Writer & critic

(Published in the 1988 exhibition catalogue 'Against Nature' - Giray Gallery, London)

Adrian Hemming’s art is a contradiction. He paints religious pictures but his viewpoint is secular. So many Bible stories have a strong story line, the meaning of which rings as true today as ever, providing a vehicle for his art. He is, however, in no way an illustrator, the idea of surface and the use of paint being as important to him as the subject matter. His technique is traditional, using layer after layer of glazes, and he is continually editing out to build up the image, so that it is a constant process of evolution. The tension resides in the duality between paint and the image, the struggle to ensure that neither submerges the other.

Joseph and his brothers is a powerful example of this duality. The title is taken from the Thomas Mann book of the same title. Hemming has chosen the moment when Joseph is being lowered into the pit. There he is, his pale body dangling at the end of a rope, facing certain death, a fact emphasised by the skulls of former victims, whilst the brothers leer triumphantly from above. One is struck both by the poignancy of the situation and by the beauty of the paint.

A pair of paintings on the subject of the temptation of St. Anthony form a dialectic between the world of the Spirit and the world of the flesh. The first, in a deliberately Old Master technique, shows the hermit being tempted by lewd women and the devils in the shape of hyenas. Framed in gold leaf, with a Baroque red swag holding the picture together, it refers deliberately to older art, as does the Italianate landscape in the background. Heads peering down on to the scene are a reference to debased and degraded putti. The companion piece is set in the exterior, rather than the interior, world, which we, the viewers, inhabit. Painted more roughly in a looser technique, it invites us to regard the reality rather than the dream. St. Anthony lies grossly naked on the ground, accompanied by a particularly unpleasant pig, symbolic of lust. The Saint desperately rings a bell to ward off the evil spirits. The watching putti are transformed into grotesque characters who bear a strong resemblance to Goya’s black paintings.

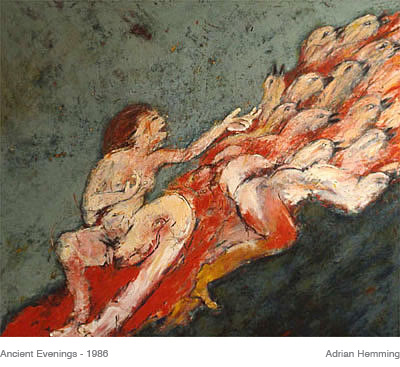

Hemming does not confine himself to the Christian religion, but draws on religious iconography in its widest sense. Ancient Evenings is titled after a book by Norman mailer and refers to the transmigration of souls. The book is set in Ancient Egypt, and Hemming’s androgynous figure has taken on something of the stylised nature of Egyptian tomb paintings. The figure’s gesture is ambiguous – it is at once one of despair and of beckoning, a farewell as well as a greeting. The arm reaches out towards a migratory flock of birds that are hurtling, lemming-like, out of the picture space, the carriers and messengers of the soul. The flesh colour of the birds is set against a blood-red stream of paint, contrasting with a complementary speckled and gouged green background. Tragedy is inherent in the picture.

For this exhibition Hemming has constructed an installation of Des Esseintes’ bedroom as described by Huysmans in ‘A Rebours’, plain and simple but costing a fortune. Within the room hangs the Baroque Temptation; on the outside wall the St. Anthony who belongs to the world of reality. It is perhaps salutary to remember that Des Esseintes, unable to assuage his ennui with decadence, ultimately looks for comfort in religion. Hemming’s’ paintings are about eternal truths.